Open the interactive report to review the analysis and do your own research

Click to view the data-set and carry out your own in-depth analysis using the interactive reporting tools

Introduction

To IPO or not to IPO? that is the question. Whether it is more profitable to risk the slings and arrows of a placing or to wait and see how the market receives it? These days I tend to ignore the barrages of broker emails and don’t get carried away by FOMO: I prefer to give a placing some time in the market before taking a position. Intuitively this feels right but I decided to go beyond heuristics and take a deeper look at the data to see if being more systematic was of merit. Does it make sense to get in early at the placing price? How do IPOs tend to behave post the placing and in their formative years? The initial results surprised me so I did a bit more digging before drawing any firm conclusions. This article is the first in a series looking to unpack some of the insights and devise actionable trading and investing strategies.

Being more of a trader than an investor these days, I increasingly use historical price action to inform my decisions: clearly as initial public offerings, IPOs don’t have that. Some time in the quoted markets is useful to get a handle on volume at price not to mention post flotation shocks, wholesale offloading of pre IPO shares as well as any issues with the placing, book building and very early stag profit taking (during Facebook’s first couple of weeks on the markets in 2012, the price dropped 27% below the IPO price amid frantic trading) . I also have an aversion to prospectus documents with their Byzantine appendices and turgid, overlong bulk. Finally, there is a good body of academic publications to evidence that IPOs tend to underperform typically by -8 to -23% (1-3).

Background to the Study

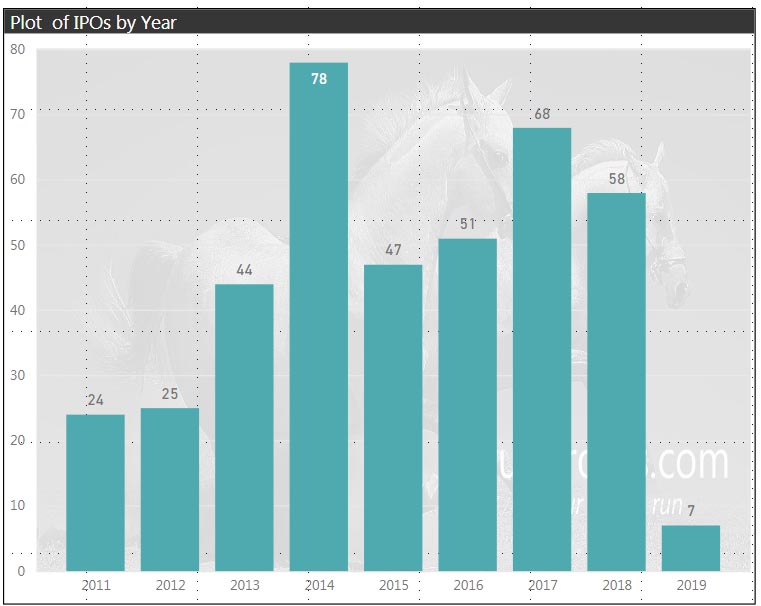

With the above in mind I went through the London Stock Exchange list of new issues and abstracted data from a set of over 3000 IPOs and placings. I wanted to avoid the GFC and the extreme volatility in its aftershock so ruled out listings before end 2010. I was also keen to look at more recent placings in the “new” ultra-low interest environment. The final set was a list of over 530 companies in the period 2011 to 2019. This was further whittled down by another 130 or so which didn’t appear in the datamining: the bulk of which seem to have delisted (some may have changed name). This article takes a quantitative look at the performance of the 408 remaining IPOs placed between 2011 to 2019. It is worth mentioning that there are some screaming frauds in those 133 that delisted (and others that were profitably bought-out): it might be worth returning to them at a later date as they will likely skew the numbers.

Let me be clear from the get-go, this is a quantitative study based on a total universe of the good, the bad and the sometimes downright ugly. It doesn't have the qualitative lens used by good fundamental analysis coupled with sector and domain expertise used when focusing on individual placings. Nor does it approach IPO placings by trying to understand the motivation behind the listing given cost, complexity and disruption to the business this causes (4). There is a lot of data here but hopefully the visualisations help tease out the value and enable some actionable observations and some compelling conclusions. My initial views and preconceptions were challenged by the data and my own conclusions unexpected. I’ve appended notes below on assumptions and omissions including not comparing to the underlying market. I also accept that this analysis would be more robust if 408 non IPO companies were chosen from the same period and the analyses compared but this task would then be in danger of becoming Sisyphean.

So does it make sense to take a stake in an IPO at the offer price?

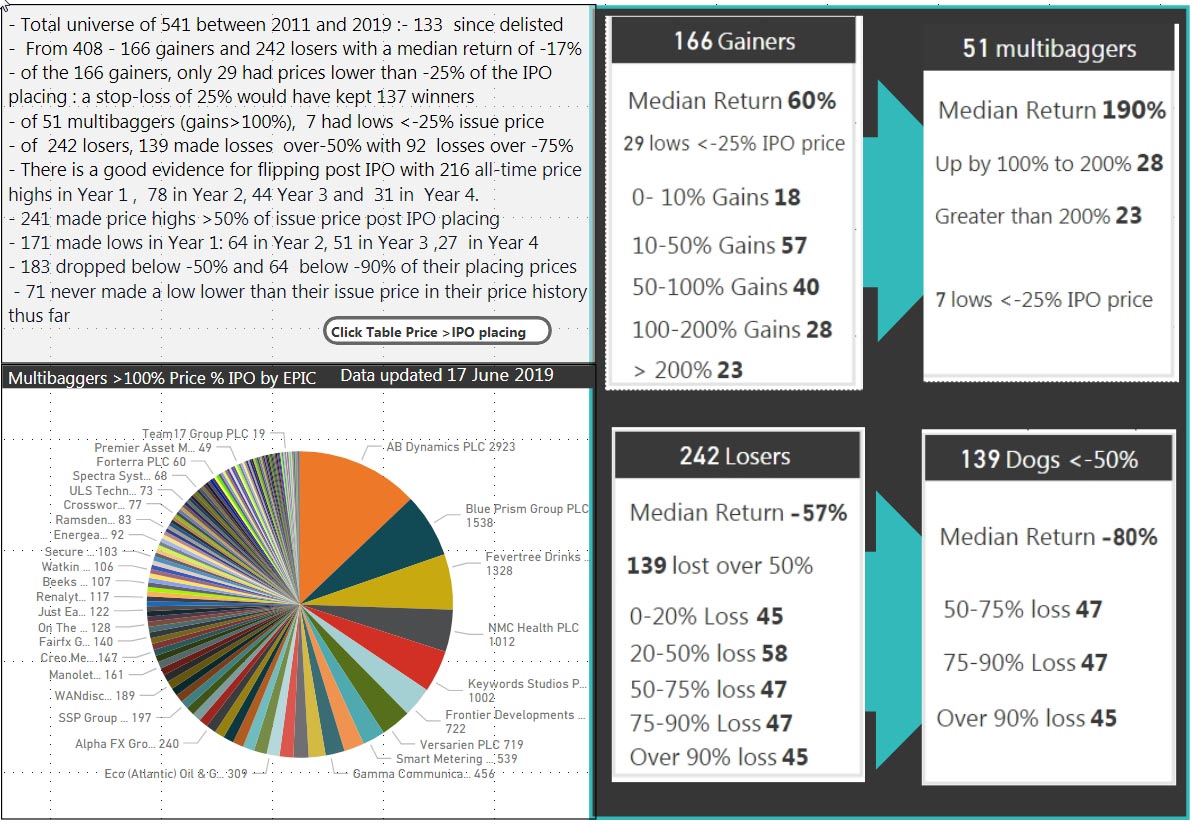

On the face of the total data, the unqualified answer would appear to be No. As in of the 408 placings studied, the median return was -17%. This pretty much ties in with the academic research and appeared to confirm my own bias. But it doesn’t tell the full story by a long shot. I did some more datamining, pulled out some historical parameters structured it in Excel and then fed it into Power BI to analyse and visualise. In my discussion below, a “multibagger” is any share that has more than doubled and a “dog” is any share that has more than halved in value.

The Topline Results

- Data mining techniques were used to derive highs and lows from the dataset, avoiding a lot of chart gazing and human error. The below summarises these results and contextualises them in terms of profit and losses.

- Of those 408 companies studied there were 166 gainers and 242 losers : a 40:60 ratio of winners to losers.

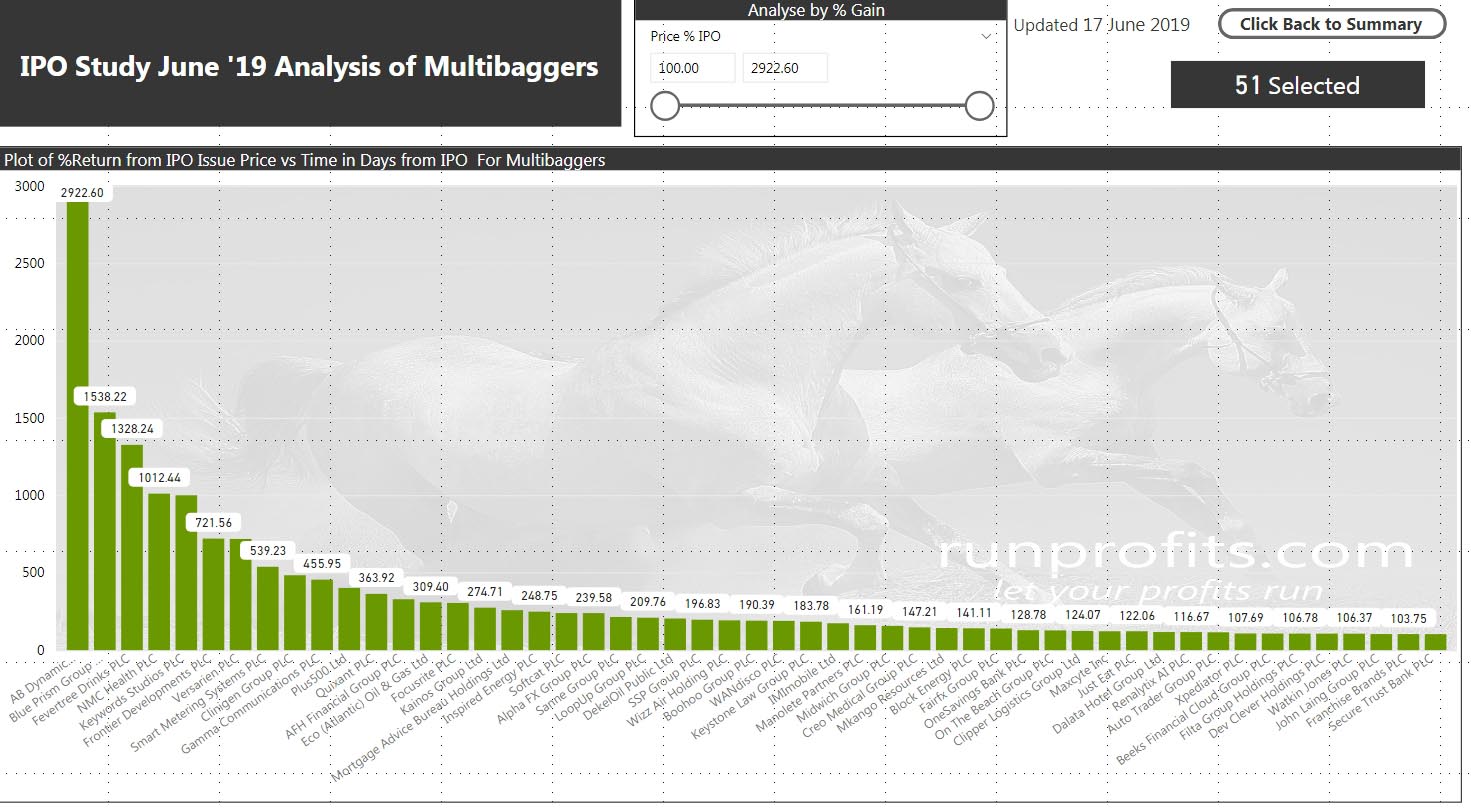

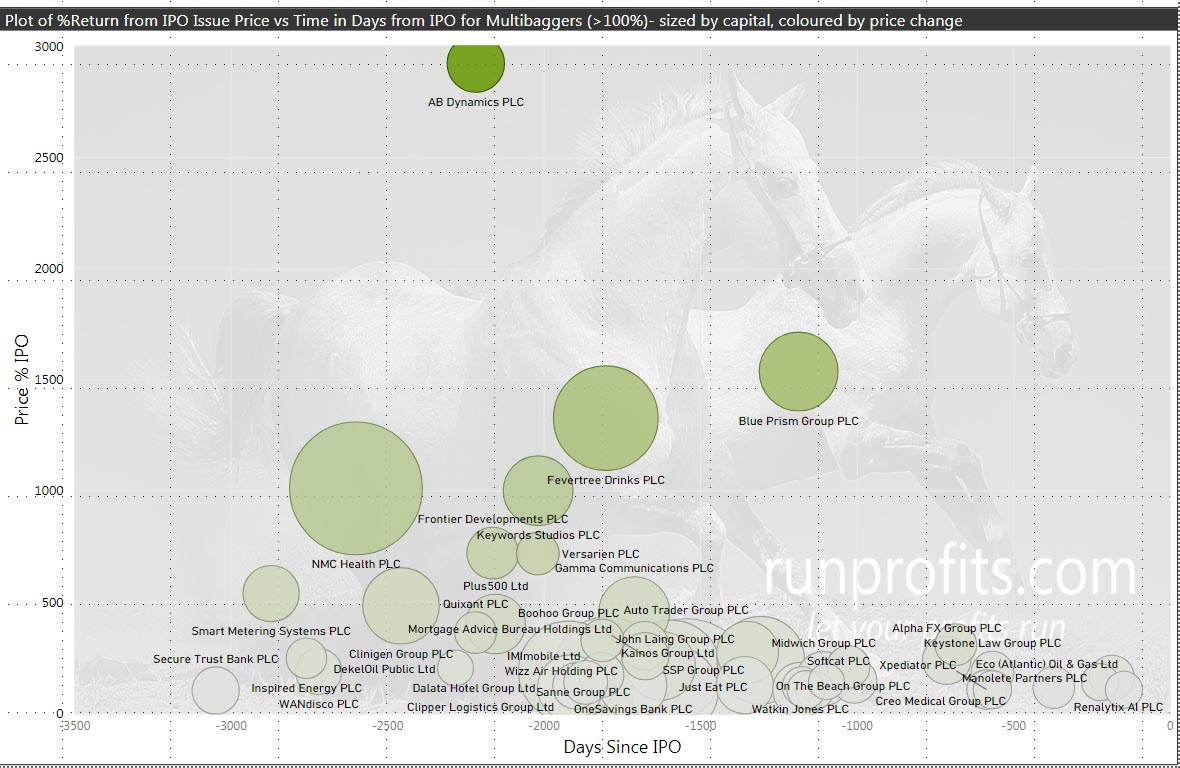

- The 166 gainers had a median return of 60% with 51 multibaggers with a median return of 190% , 23 of which made more than 200%.

- Of the 166 winners , 71 never made a low below their offer price and only 35 made price lows lower than 25% below their offering price.

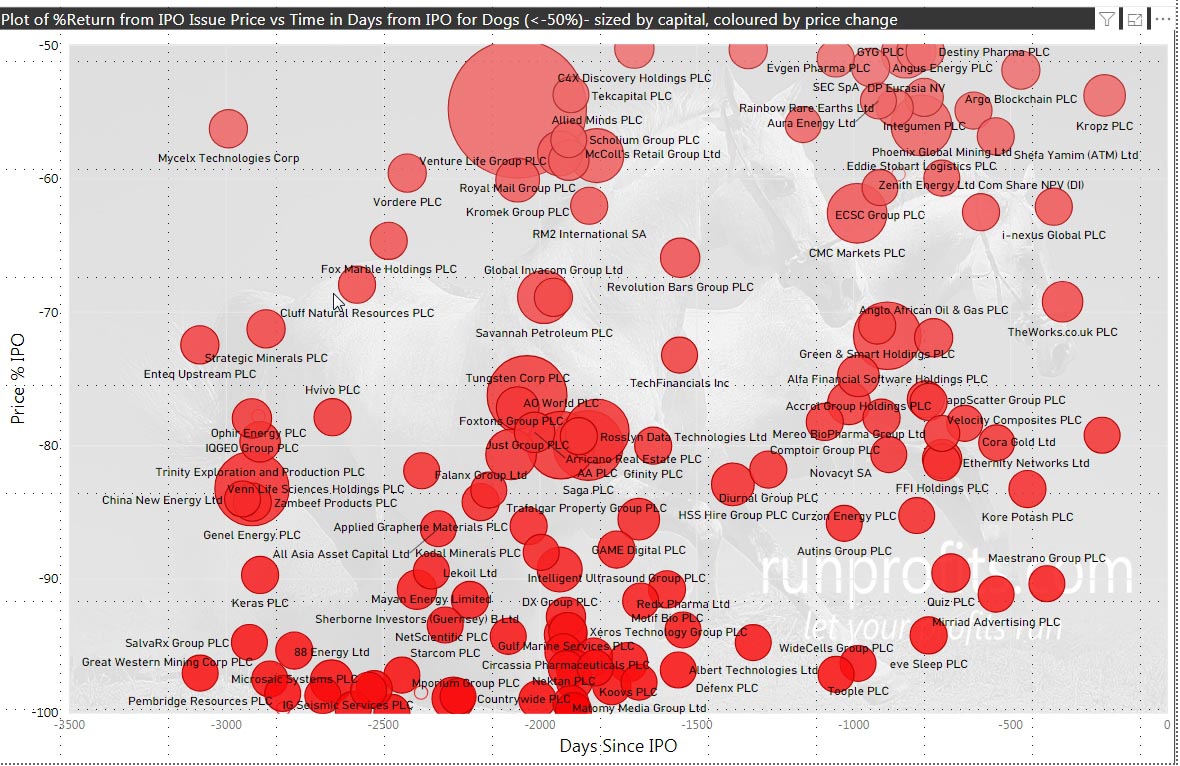

- The 242 losers had a median return of -57% with 139 dogs losing over 50% and 45 with over 90% loses

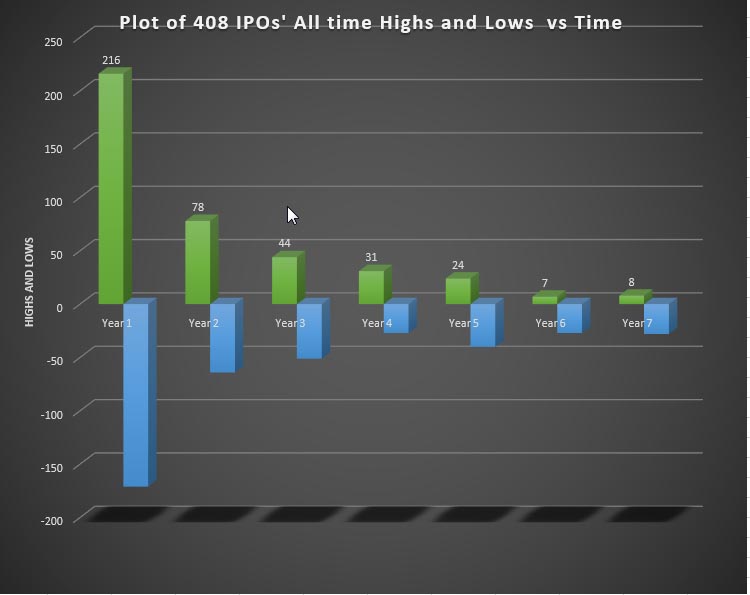

- 216 of the 408 made their price highs in Year 1 after the placing, with 78 in Year 2, 44 Year 3 and 31 in Year 4.

- Only 10 of those 216 highs in Year 1 made a high below the IPO placing price, the rest were in-profit.

- 241 made price highs greater than 50% of the issue price at some point over the total duration studied

- Conversely 171 made lows in Year 1, 64 in Year 2 with 52 in Year 3 and 27 in Year 4.

- 335 made lows lower than the placing price over the total duration with 183 making lows lower than 50% of the placing price.

Some observations and So what?

- Winners generally kept winning with 31% of winners winning really big (up to almost 3000%)

- Many of the losers went on to lose a lot with 38% of losers losing really big (>75%)

- A stop loss of 25% would have kept 143 of the 166 winners in play and only stopped-out 7 of the 51 multibaggers while removing 215 of the 230 losers.

- Given the number of highs in the first year, there is very good evidence of flipping in Year 1 possibly by both institutions and private investors.

- Taking a position in an IPO looks to be more of a traders’ game than an investors’ one (with all the caveats on quality of fundamental analysis)

Rabbits and Assassins

This suggest some potential strategies around IPO placing that help to mitigate risk and look to capture the multibaggers (and try not to let them go) while releasing the dogs early before being thoroughly savaged.

The numbers suggest that allowing the price action post-placing to dictate one’s strategy seems to make sense i.e. assume taking a position in an IPO issue is a trade until price proves it to be an investment. Then let execution strategy and risk management navigate the price trajectory post-placing. This of course pretty much true for any trade or investment but what may be peculiar with IPOs is that once forged in the fire of price discovery, public markets rapidly resolves the good from the bad: the multibaggers from the dogs even as large holders of the original issued equity play out their hands. That the initial perceived value, the issue price, is a discrete price and not a range may give a very defined selling point. This may well skew behaviours and exaggerate price performance as most participants anchor to the same price point at least in the early years.

This study shows that a stop loss of 25% retains 86% of the winners and more importantly almost 90% of the multibaggers. Given the sample size and duration of the study these seem like a sensible parameter to use in trade execution. Building positions by adding to winners and letting go of losers (defined at least by a stop loss) concentrates capital in the best performers.

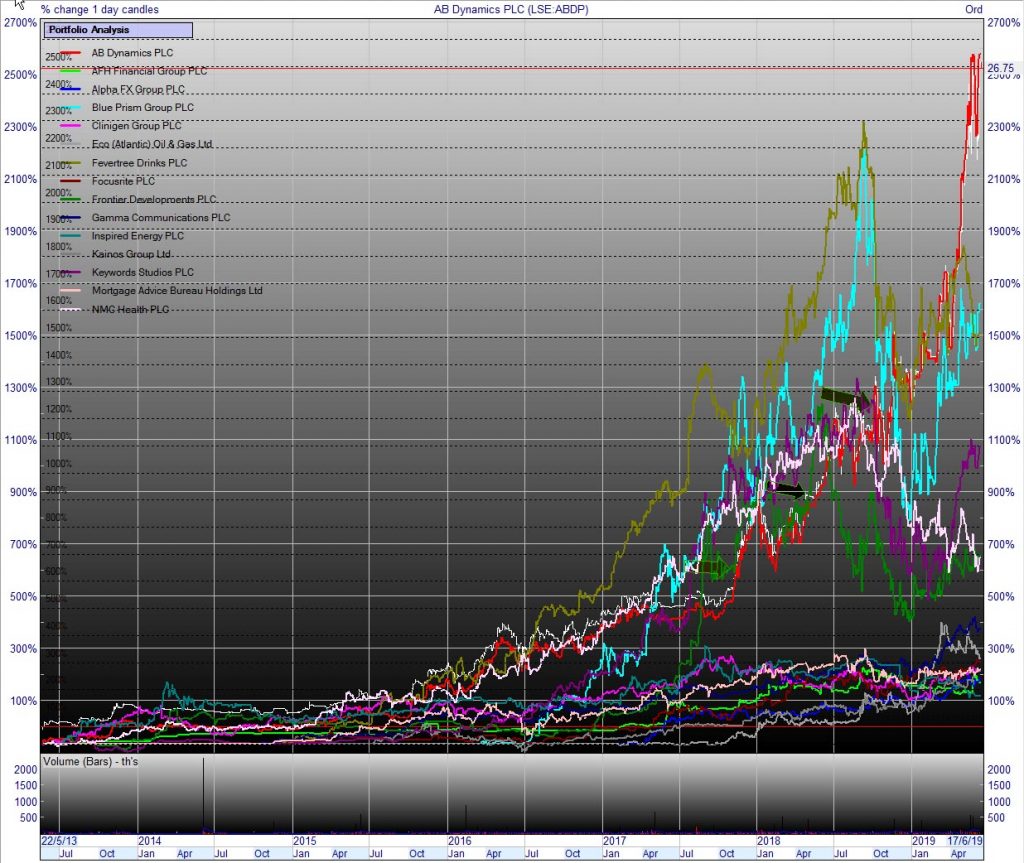

To invoke Lee Freeman-Shor’s investing behavioural types (4), one needs to be an assassin and not a rabbit with IPOs - executing losers remorselessly. Again this is all good discipline and trade execution but the lack of historical data with IPOs adds additional uncertainty compared to long standing publicly quoted companies with years or even decades of published accounts. That risk can bring the huge rewards evidenced by AB Dynamics (+2922%) or Blue Prism (+1538%) which convert pre IPO promise into real growth and momentum or alternatively can lead to wipe-outs like Maistro or Block Commodities (both -99.8%)

Given the number of highs in Year 1, flipping is also a viable trading strategy with different risk parameters and expected returns.

The Voting and Weighing Machines

This comes back to the original question; should I take a stake in an IPO placing and is there really a danger of missing out? Only a few of the multibaggers ever got cheaper than their initial placing IPO price but all of them went on to make most of their returns several years after their placing dates. Relative to the rewards offered later on, the difference between the issue price and prices in early years suggest it might make more sense to wait for performance in the market rather than buying in the placing (Figure 7.). Indeed. a number of IPOs which did go on to be multibaggers went through periods of underperformance in the initial years and did offer better buying opportunities (BOO, BLOW, LTG, WAND). This echoes Ben Graham’s observation that in the short-term markets tend to be voting machines while in the longer term they are weighing machines. While charts are always easier to read from right to left risk management using a stop-loss should work with the majority of nascent multibaggers

The concentration of highs in Year 1 may have multiple sources. Institutional and private investor flipping may account for much of it. It is often difficult to predict the intentions of large private equity backers/major shareholders beyond lock-in periods but these can have major impacts on price performance. This is particularly true when liquidity is low owing to initial large institutional holdings. Equally price discovery in the market and changes in market sentiment may greatly impact early performance (especially when pre IPO hype gives way to even mild disappointment post-placing). An increase in the number of IPOs issued is often used to infer periods of exuberance of the overall market with potential pseudo-market timing effects (1). Finally, IPOs predicated on inflated/invented financials and sometimes overt fraud can be difficult to detect but are precipitous once discovered.

While none of the above is rocket science, the numbers do suggest that taking a position in an IPO is better viewed as a trade while an investment may be better made post IPO when the initial few years of flipping, disappointments and price discovery have played out. These conclusions are made within the obvious caveats that more rigorous analysis of individual placings should enhance success and root out the more obvious dogs.

Figure 7 Price History of the Top 15 Multibaggers Post IPO

Conclusion.

What is very clear from the data is that there are good chances of making profits from trading an IPO position bought at the placing by selling in Year 1: timing really does work. The real rewards come from allowing good trades to become better investments , trade management and the use of stop losses will support that and prevent the converse which is too often the case when holding on to, or even adding to, losers. My opinion on IPOs has changed, from now I’ll take an informed position but trade it until it proves otherwise.

In the next article in this series I will dive into the multibaggers in more detail and characterise what good looks like as well as the importance of trade execution and management.

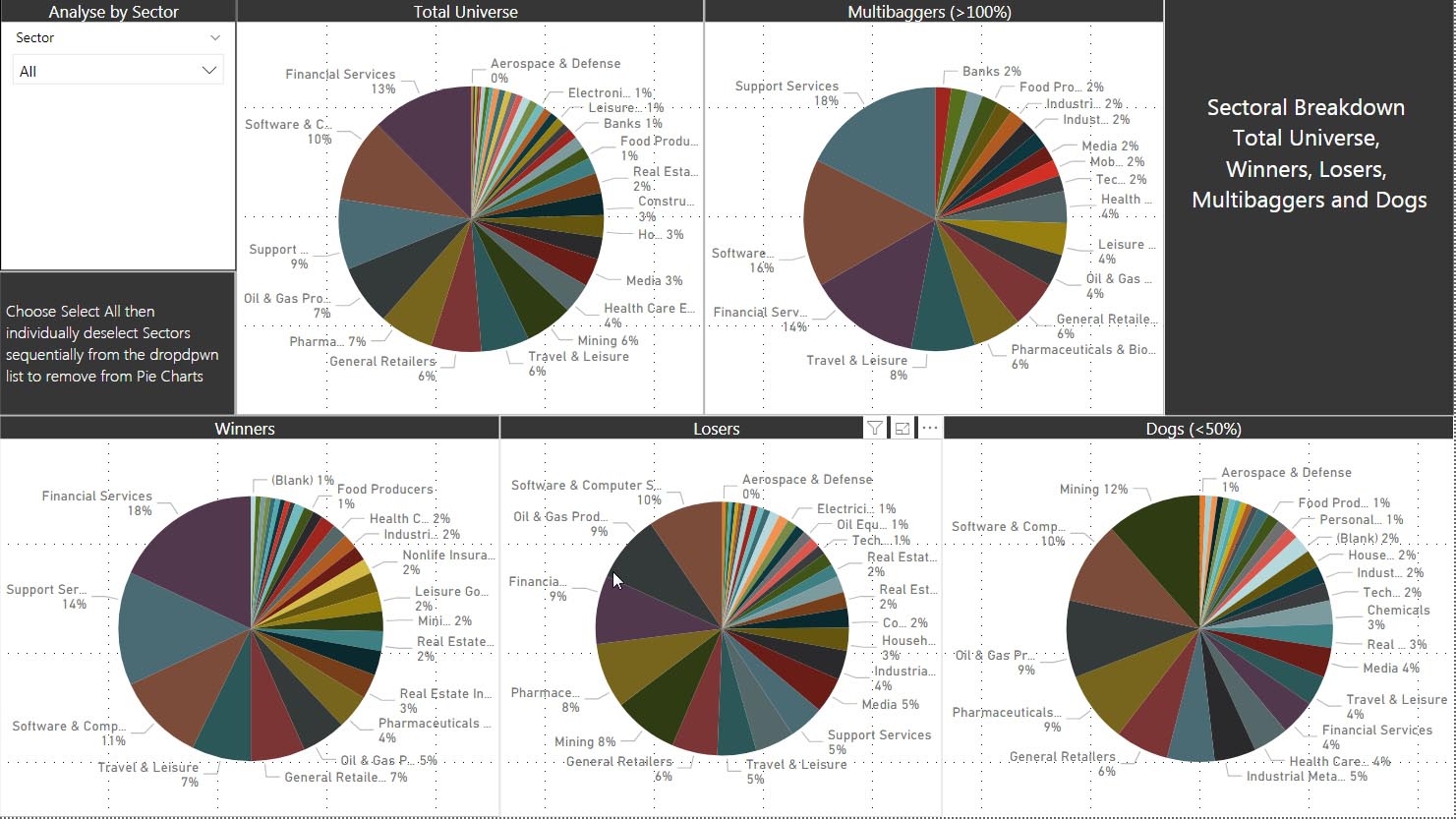

Appendix: A note on Sectors, Countries

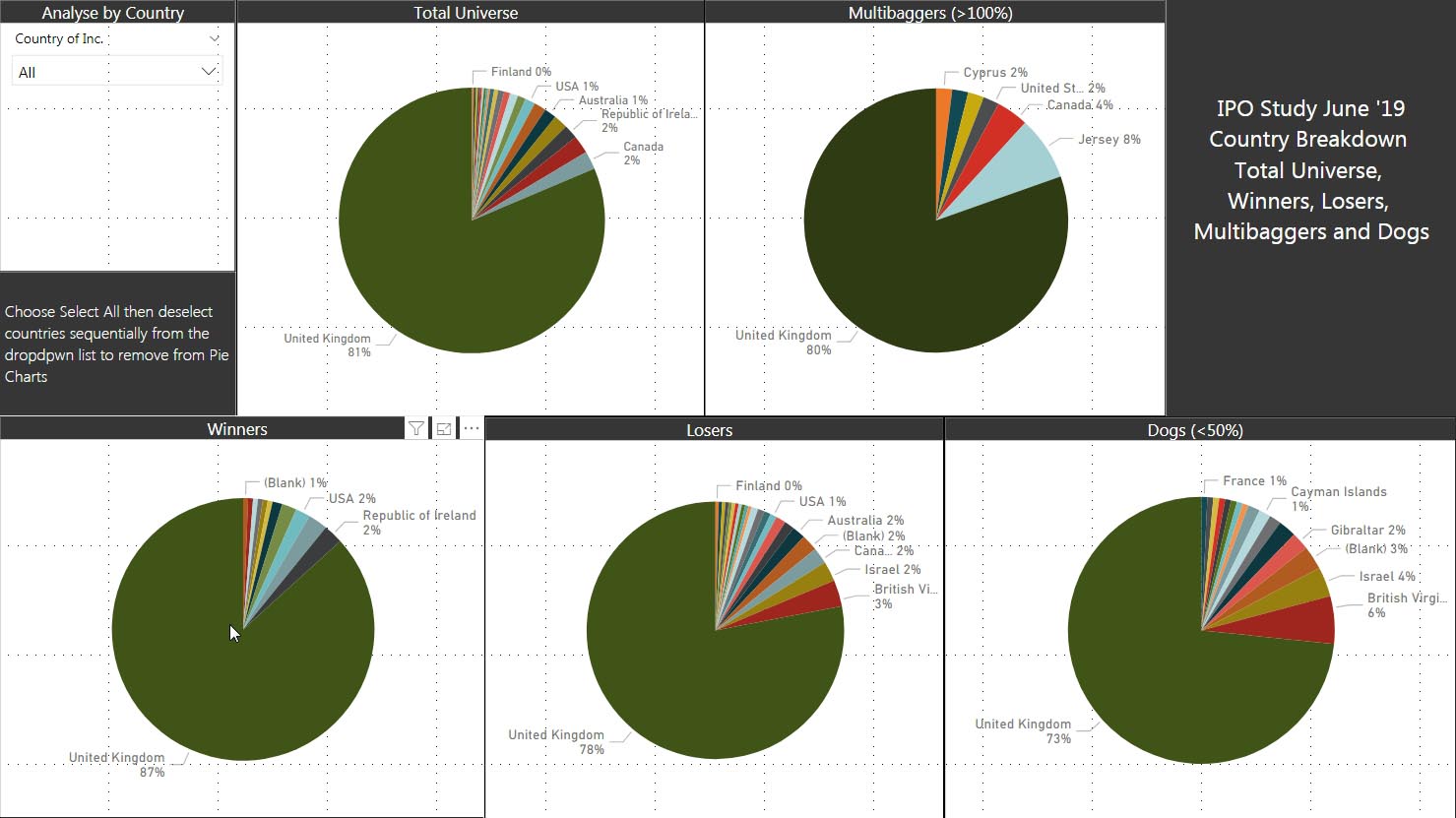

The total universe of 408 was analysed by sector country and market as were the winners and losers to examine sector and country over/under-performance. Junior oilers and miner are fairly notorious for overpromising and under-delivering with sometimes spectacular losses. Many investors will shun companies from some countries owing to track records of frauds and limitations on prosecution in the event of fraud.

Figure 8 shows that more of the winners came from Financial Services, Support Services with an even more pronounced concentration of Support Services and Software companies in the multibaggers. Mining and oil and gas producer did concentrate in the losers with the ratio of mining doubling from 6% in the total universe to 12% in the dogs;

Figure 9 shows a similar segmentation by country, I suspect that this would change further if the 130 delisted companies were included since it contains several from Israel and China which have proven to be frauds. The plot shows a doubling (albeit from a low base ) of Israeli and BVI companies in the dogs : the percentage of UK companies increased from 81% in the total universe to 87% in the winners and decreased to 73% in the dogs. This does seem to confirm the bias against companies from these countries.

Notes

- There are 133 companies that listed in that period and subsequently delisted in the intervening years: many of these have been acquired (Poundland, Jimmy Choo, TSB) while many more ( Naibu, MySquar, Patisserie Valeria) were frauds. I've excluded that list from this analysis but may revisit later to update the data set although that needs much qualitative analysis

- the performance of the placings have NOT been corrected relative to the underlying markets – so at the time of this analysis, from 2011 to 2019 the FTSE All-Share has risen 31.6% while the AIM All-Share is up just 1% and the FTSE 100 up 15%. Given the different timescale of the placings, the relative corrections to underlying markets would have been pretty time consuming.

- Relative performances have been derived using time from IPO date: this will be skewed to some extent by more recent data: 30% of the total sample were placed in the last 3 years (removing these drops the median return to -24% for the total universe )

Notes

- There are 133 companies that listed in that period and subsequently delisted in the intervening years: many of these have been acquired (Poundland, Jimmy Choo, TSB) while many more ( Naibu, MySquar, Patisserie Valeria) were frauds. I've excluded that list from this analysis but may revisit later to update the data set although that needs much qualitative analysis

- the performance of the placings have NOT been corrected relative to the underlying markets – so at the time of this analysis, from 2011 to 2019 the FTSE All-Share has risen 31.6% while the AIM All-Share is up just 1% and the FTSE 100 up 15%. Given the different timescale of the placings, the relative corrections to underlying markets would have been pretty time consuming.

- Relative performances have been derived using time from IPO date: this will be skewed to some extent by more recent data: 30% of the total sample were placed in the last 3 years (removing these drops the median return to -24% for the total universe )

Topline

408 IPOs from 2011 to 2019 were analysed quantitatively: the median return was -17% with a 60:40 split of losers to winners over the time period. This fits with published academic studies of IPO performance . A deeper analysis of the numbers gives more insight on opportunities and the role of stop losses in converting trades into very profitable investments some which yielded several thousand percent returns.